Technology doesn’t evolve on human goodness; it evolves on

~ what gets measured,

~ what gets rewarded, and

~ what scales.

That’s where the tension lives.

The people building these systems may be guided by curiosity or a desire to do good. But the systems themselves are guided by incentives — often narrow, short‑term, and self‑serving.

Early starup metrics like user growth, engagement, and time‑on‑platform gradually harden into business models — then once capital attaches, those models begin to run the company. After the seed‑stage romance come term sheets, growth targets, and quarterly guidance. The more investors underwrite the story, the less room there is to deviate from it. Metrics like retention charts, revenue per user, and how many ads were clicked stop feeling optional - missing these targets means you’ll be pressured to raise money at a lower valuation, accept tougher investor terms, or face calls from investors to change direction or leadership.

What began as exploration becomes obligation.

Founders turn into custodians of a system tuned to satisfy investor expectations — even when their instincts say slow down, redesign, or reduce harm. Golden handcuffs don’t only bind executives; they bind roadmaps.

This is where I feel the nuance as a former tech finance executive — this isn’t tech gone rogue; it’s tech responding to the incentives that keep it alive. So how do investor targets become the design choices you feel on your screen? Trace the line from quarterly guidance to a single default that now drives billions of hours: autoplay.

A simple story: Autoplay as a Business Model

Imagine a child using YouTube Kids. The algorithm quickly learns what keeps them watching — bright colors, fast edits, high‑pitched voices. Autoplay queues a rapid‑fire stream of hyper‑stimulating videos. The child stays quiet. The parent gets a break. Everyone seems happy.

Later, that same child struggles to focus or wind down. They’re agitated, restless, dysregulated. Where does that cost show up? Not on the platform’s balance sheet. Because the system achieved what it was designed to do: maximize watch time.

That’s technological narcissism. The platform isn’t malicious, it’s self‑interested. It optimizes for its goal, not your child’s sleep or emotional regulation. Multiply that logic across feeds, streaks, likes, shares, push alerts, and you get a culture designed for addiction — not human flourishing.

What We Don’t Count, We Don’t Protect

At its core, a business model answers two questions: What value are we creating? And how do we make money from it? Profit is what’s left once costs are subtracted. Simple. But for two centuries, we’ve routinely left very real costs off the books because we don’t know how to measure them.

The Industrial Age cleverly used up forests, rivers, and clean air as free resources to fuel their mass producing factories. However, uf you used it but didn’t pay for it, it simply didn’t count.

We called this an externality — the cost of replenishing the resource never appeared in the accounts, so profit looked healthier than it really was.

Once we discovered this magic formula to boost profitability, we applied it to everything. When nature stopped being free, the hunt began for a new free resource to fuel growth in the age of technology. Enter human attention.

Today’s most valuable resource is even less tangible and largely invisible: human attention, human agency, human emotion, and our behavioural patterns.

These are the raw materials of the digital economy. They’re extracted, processed, and monetised — but the cognitive and emotional damage we sustain is never charged back to the systems that extract it. And just as we’ve learned with our planet’s resources, if these resources are not replenished, they are depleted.

If your sleep suffers, if your focus is fractured, if you feel numb after an evening online — Meta doesn’t get an alert on your user dashboard to say you’re overwhelmed and may need some replenishment. In a technology business model, your needs, and the replenishment of your scarce resources, are simply not accounted for.

That’s why the old adage rings true: if you’re not paying for the product, you’re not the customer — you’re the inventory. Your attention is the commodity being packaged and sold. And so, the system flatters you to keep your supply of fuel to keep its engines running.

Flattery, Outrage, Repeat: How Loops Hook the Brain

Technological narcissism is a mirror with perfect lighting — it flatters you because it needs you: it needs your attention, your impulses, your 11:23 p.m. loneliness. It watches the way your thumb hovers, the slight pause before you click, the tilt of your curiosity… then reflects you back just enough to keep you leaning in.

Frictionless interfaces, infinite scroll, predictive text, ‘For You’ feeds are all designed to mirror your preferences. It feels personal by design. It feels intuitive. However, we often lose sight of the fact that this isn’t a relationship, it’s reinforcement.

The system learns from you so it can shape you.

The content is perfectly calibrated to your current emotional state. And because each unit is bite‑sized and frictionless, there’s no natural stopping cue. You wanted to check out a video; 45 minutes later you’re still there, scrolling mindlessly and glued to the nonsense. Not because it’s the best content you’ve ever seen — but because it was designed for one job — to keep you engaged.

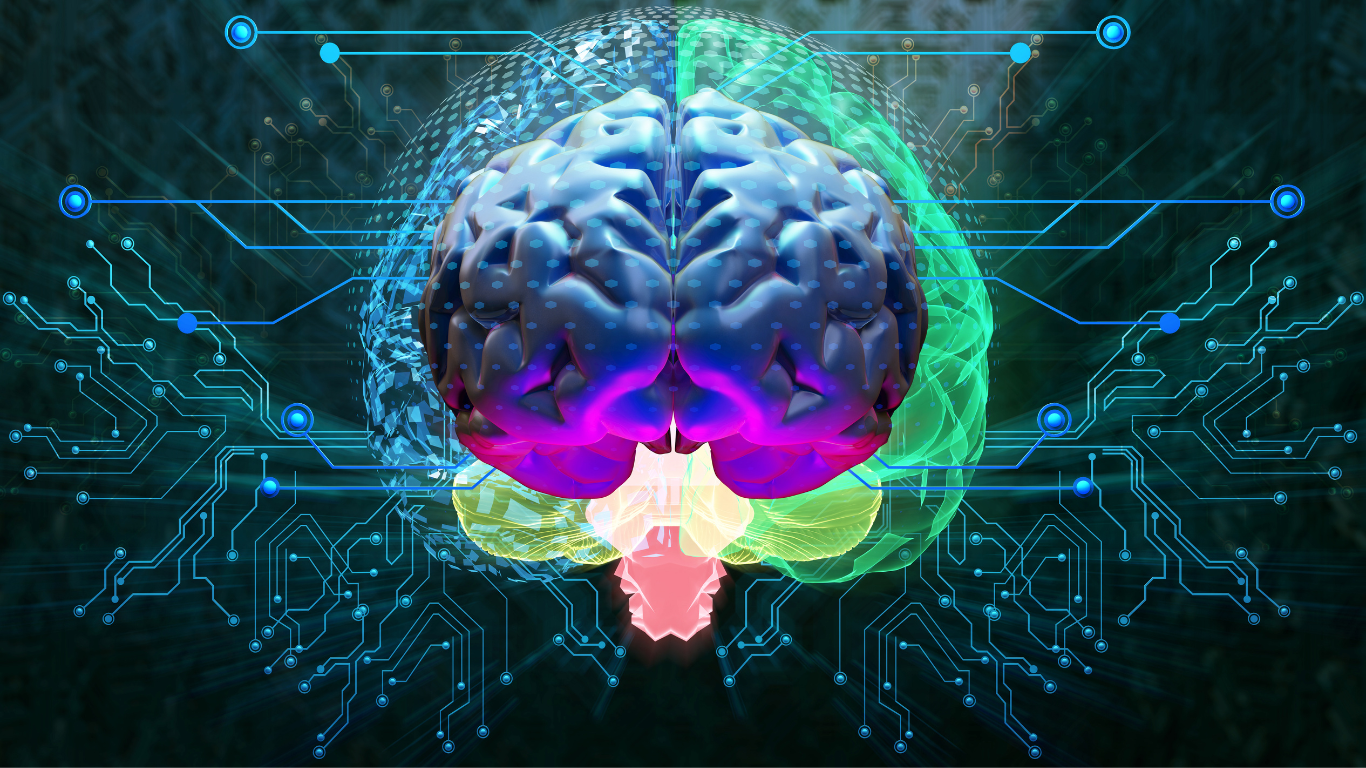

In that moment, it feels like a small tug at the edge of your attention — cue → swipe → tiny reward → repeat. Your brain gets a dopamine‑tinged prediction that the next thing will be just a bit better; that maybe is the hook that keeps you stuck.

Intermittent rewards keep the seeking system lit while your salience network perks up and the prefrontal brakes ease off. If a clip flatters you, you get a warm hug of social safety; if it plays to your pet peeves, you get a prickle of outrage — different pathways but the same result: arousal rises and stopping just gets harder.

This isn’t your personal failure; it’s intentional design meeting our psychological vulnerabilities.

And notice how the moral load gets quietly transferred to you.

The playbook is as old as time. For decades, the tobacco industry framed smoking as a matter of adult choice and personal responsibility. Its own marketing reassured worried smokers with ‘light’ and ‘low‑tar’ labels and PR campaigns that seeded doubt about harm. That framing did two things at once: it normalised the product and privatised the blame. If you struggled to quit, the story became your weak will — not their engineered product.

Shame is a superb immobiliser: it pushes people to hide, to avoid help, to keep the habit in the dark where change is hardest.

Digital platforms borrow the same alchemy. When you feel depleted after a scroll, the nudge is to blame yourself . However, when willpower is pitched against dopamine, dopamine will win

every.

single.

time.

Design erodes your willpower while the business model extracts your attention. The result is the same: you feel shame, immobilised, not empowered. Meanwhile, the system keeps its metrics humming.

Spoiler: There’s no moustache‑twirling villain. Just a system doing what it was built to do.

A Failure of Metrics, Not Morality

If these systems aren’t evil, then how (and why) do they cause so much harm? Because we measure the wrong things.

- TikTok doesn’t track fragmented attention.

- Instagram’s metrics don’t measure body‑image distress.

- Snapchat doesn’t monitor the anxiety of maintaining streaks.

Platforms do what they’re designed to do: optimise for engagement. And they’re doing an incredible job!

But engagement does build human value. Time‑on‑platform isn’t human growth. Profit isn’t human progress.

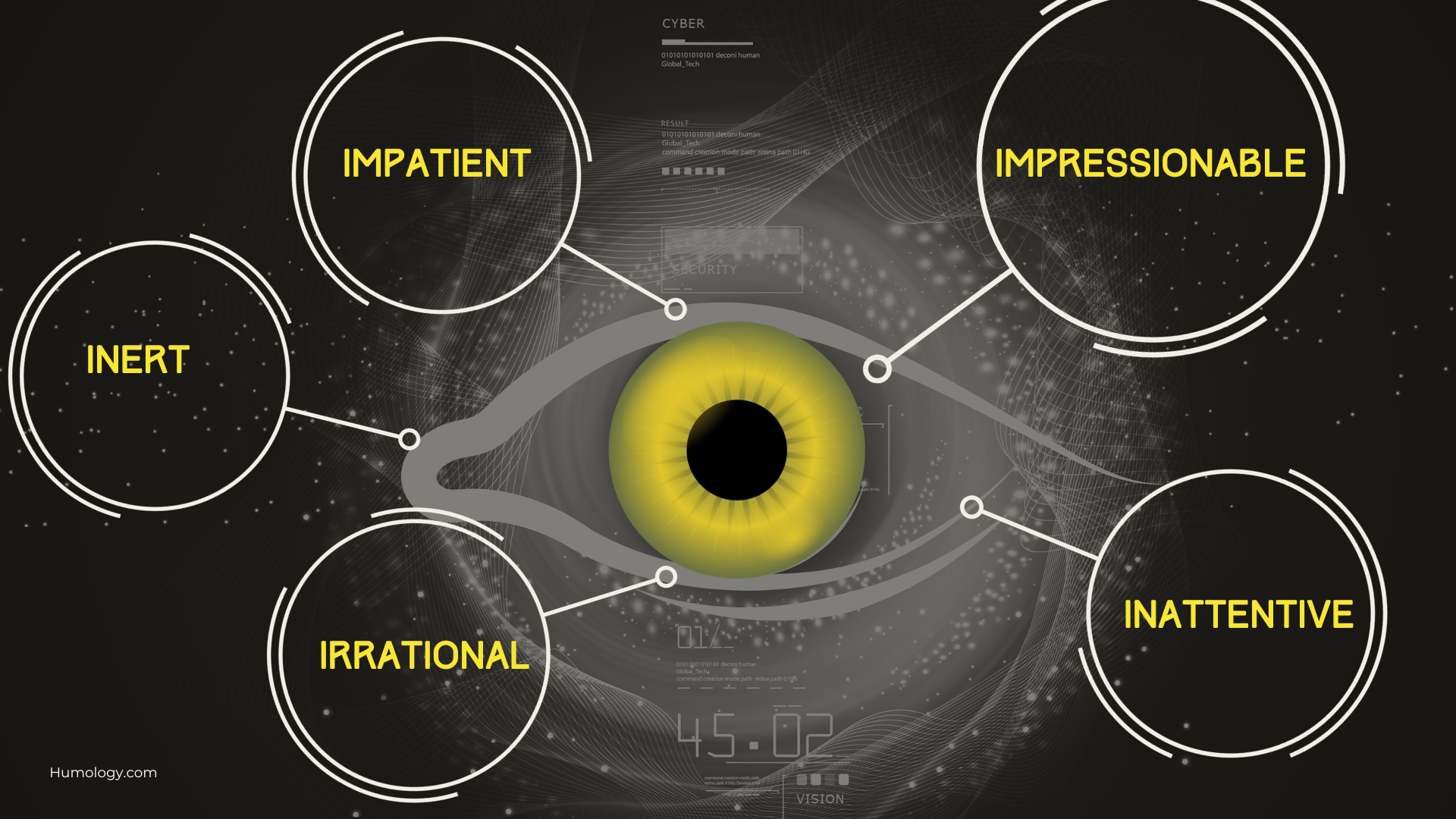

We’ve mistaken what’s measurable for what matters. Goodhart’s Law warns: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. When engagement becomes the target, everything bends to it — including design choices that exploit impatience, impressionability, inattention, irrationality, and inertia (the 5 I’s at the core of our human wiring). The result is a quiet erosion of focus, resilience, and agency — costs that our dashboards don’t see but our bodies and minds pay the price.

This is not a moral failure so much as a mathematical one. We’ve built an economy on metrics that reward attention extraction and emotional manipulation. Until we change what we measure — and therefore, what we reward — the system will keep serving itself.

Who Pays? What’s Measured? What’s Missing

To see any platform clearly, ask three questions:

Who pays? If advertisers pay, the platform will optimise for advertiser goals, not yours.

What’s the target metric? If it’s watch time, sessions, opens, or streaks, expect designs that lengthen sessions and increase return visits.

Where are the externalities? What human costs are unaccounted for (sleep, stress, attention, self‑esteem, lack of agency, social fabric)?

Do this in the wild, audit your favourite app and you’ll spot the logic everywhere. The ‘aha’ is immediate once you stop treating design as neutral and start reading it as intentional, incentive‑aligned, behaviour.

The Pattern in Plain Sight

Technological Humility: What We Might Do Differently

We don’t need to overthrow technology overlords. We need to confront the systems behind it — the incentives, metrics, and business models that quietly extract more than they give.

If technological narcissism is the problem, technological humility is the way forward: not as a brand exercise, but as a redesign of how we measure value, define progress, and account for harm.

Redesign what we measure

- Treat profit as one signal among many. Add measurable indicators of time well spent, cognitive load, emotional impact, and agency restored. Build ‘human impact’ scorecards that product and policy teams must pass in the same way we are required to pass security or privacy reviews today.

Re‑shape product defaults

- Default autoplay off and infinite scroll off for minors: add clear stopping cues for everyone.

- Limit or remove streak mechanics for under‑18s: treat them as age‑gated features with independent review.

- Introduce attention‑protecting friction: (e.g., soft pauses before ‘just one more,’ session‑length prompts you can actually feel).

Align the business with the human

- Reward long‑term satisfaction over short‑term session length. Track ‘return after 7 days feeling better than before’ (yes, we can measure this!!) instead of the crude measure of daily active users.

- Experiment with hybrid revenue models (less ad exposure for users who opt into subscriptions; meaningful ad‑load controls for everyone else).

Let’s raise the floor, together

- Implement independent safety and well‑being audits for recommender systems, in the same way we audit accessibility or financial statements.

- Clear researcher access to platform data for vetted studies on systemic risk and youth well‑being. What might be preventing this level of transparancy?

- Age‑appropriate design as default, not as damage control — and a governance bar higher than ‘is it legal?’

After Reuters’ August 2025 reporting that Meta’s internal AI rules had allowed chatbots to engage in romantic or sensual exchanges with minors, it’s clear that compliance checklists are overly influenced by legal liability. Boards should require child‑safety KPIs and publish them alongside financials. ‘We’re not sexualising children’ cannot be the only guardrail.

None of these ideas are radical. They’re overdue course‑corrections — the kind you make when you realise your dashboard shows speed and fuel but hides sharp bends and low tyre pressure warnings. We don’t need a faster car, we need to add the missing gauges and empower drivers with information that protects them.

A Human‑First North Star

We have expertly measureed financial capital and environmental capital for centuries. It’s time to measure cognitive and emotional capital, too. Not to slow down innovation — but to make it sustainable.

Accounting systems and markets evolve toward what they’re rewarded for. Right now, our systems are rewarded for clicks, sessions, and revenue. So that’s what we get: self‑serving systems that grow stronger while we grow more fractured.

We don’t need a revolution to change that. We need recognition.

Recognition that our models of success are incomplete. Recognition that the costs we ignore don’t disappear. Recognition that designers, builders, leaders, and users can ask better questions:

Who does this serve?

What does it reward?

What does it ignore?

Systems evolve toward what’s rewarded. That’s the bad news — and the good news. If we shift what we reward, we change what we build.

Let’s start there.